Dat is inderdaad ook iets wat je zou kunnen nagaan. Bijv door een leeg filter op zo'n bak draaien. Is wel iets lastiger met water verversen denk ik, want je oppervlakken mogen niet te lang droog staan. Ik twijfel o.a. hierom nog of ik misschien niet beter elke 3 dagen de filters in schone emmers kan doen. Dan krijgt de variabele "opbouw biofilm bak" minder invloed op de metingen.

Je gebruikt een verouderde webbrowser. Het kan mogelijk deze of andere websites niet correct weergeven.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een browser zoals Microsoft Edge of Google Chrome te gebruiken.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een browser zoals Microsoft Edge of Google Chrome te gebruiken.

Filtermedia test opstelling

- Onderwerp starter DanielHoogland

- Startdatum

Meer opties

Who Replied?LaLizzerd

Well-known member

In de andere bakken staan de oppervlakte ook droog tijdens een waterwissel toch? Een controlebak zou dezelfde 'behandeling' moeten ondergaan als de andere bakken.Dat is inderdaad ook iets wat je zou kunnen nagaan. Bijv door een leeg filter op zo'n bak draaien. Is wel iets lastiger met water verversen denk ik, want je oppervlakken mogen niet te lang droog staan. Ik twijfel o.a. hierom nog of ik misschien niet beter elke 3 dagen de filters in schone emmers kan doen. Dan krijgt de variabele "opbouw biofilm bak" minder invloed op de metingen.

Wanneer je de controlebak opeens op een andere manier gaat 'behandelen' is het een ander experiment/test geworden.

Ik ben het met je eens dat de invloed van plantenfilters testen ook eens leuk zou zijn om te doen. Alleen, planten verrichten andere functies in een ecosysteem dan de microben in een biofilm. Ze zijn geen vervanging voor biologische filtratie. Als je dit verduidelijkt wilt zien, wil ik er best over uitweiden. Maar ik ben nu even op m'n werk. 😛doe dan ook een bakje met aquaponic dan zullen we zien dat de filters overbodig zijn denk ik

behalve goed is om vuil te verzamelen

Klopt. Blijkbaar heb ik je de indruk gegeven dat ik de ene bak anders zou behandelen dan de andere, maar dat is natuurlijk niet de bedoeling. 🙂In de andere bakken staan de oppervlakte ook droog tijdens een waterwissel toch? Een controlebak zou dezelfde 'behandeling' moeten ondergaan als de andere bakken.

Wanneer je de controlebak opeens op een andere manier gaat 'behandelen' is het een ander experiment/test geworden.

Ik ga denk ik (iig in de eerste ronde) geen "controle" doen zonder filtermateriaal. Zelfs het slechtste filtermateriaal geeft meer biologisch actief oppervlak dan enkel een kale bak, dus de "trend" in relatieve resultaten is bij voorbaat voorspelbaar. (Ook hebben anderen al eens op lege bakken getest.) Het is wat mij betreft interessanter om te kijken of de resultaten van aquariumscience.org te herhalen zijn.

Elke waterverversing schone emmers doen geeft de variabele "beïnvloeding biofilm bak" de minste voet aan de grond. Als je dat niet doet en je wacht een keer 5 minuten langer met emmer B vullen t.o.v. emmer A, waardoor er baccies buiten de filters sterven.... ook als de invloed daarvan beperkt is, moet je zulk geneuzel niet willen. Dus liever schone emmers klaar hebben staan, op temperatuur en alles, en *plop* de filters overplaatsen. Daarna kun je de oude emmers schoonmaken, etc. 🙂 Geeft wat meer werk maar het is wel zo consequent.

dus wat doet een biologische filter meer dan een planten filter????? planten filter neemt amonia op en nitraat een biologische filter ze de boel aleen omIk ben het met je eens dat de invloed van plantenfilters testen ook eens leuk zou zijn om te doen. Alleen, planten verrichten andere functies in een ecosysteem dan de microben in een biofilm. Ze zijn geen vervanging voor biologische filtratie. Als je dit verduidelijkt wilt zien, wil ik er best over uitweiden. Maar ik ben nu even op m'n werk. 😛

Laatst bewerkt:

Zoveel vraagtekens! Wat een nieuwsgierig Aagje ben jij! Maar dat is alleen maar leuk want het geeft mij een vrijbrief om lekker veel tekst naar je toe te smijten.?????

Wat een fijne avond dit!

Wat een fijne avond dit!Kijk, dat is natuurlijk de vraag der vragen.dus wat doet een biologische filter meer dan een planten filter????? planten filter neemt amonia op en nitraat een biologische filter ze de boel aleen om

In het kort komt het erop neer dat planten weliswaar wat dingen uit het water snoepen, maar dat zij voor veel voedingsstoffen afhankelijk zijn van het werk van talloze soorten bacteriën. Er zijn niet alleen "autotrofe", nitrificerende bacteriën (de concurrenten van planten; voor wat deze groep betreft heb je gelijk dat planten vergelijkbare functies kunnen vervullen) maar minstens zo belangrijk: er zijn ook "heterotrofe" bacteriën. Die zijn zelfs in de meerderheid in je bak, en toch zie je in filterdiscussies over deze groep bacteriën maar weinig terugkomen. Heterotrofen verwerken alles wat los en vast zit aan (met name) organisch materiaal; stoffen die in onzichtbare, opgeloste vorm verkeren, maar uiteraard ook de "ruwe", zichtbare vormen zoals de afgestorven blaadjes, voer dat is blijven liggen, vissendiarree etc... Met enkel planten heb je simpelweg geen functionerend ecosysteem. Zonder aanzienlijke kolonies bacteriën stapelt een reeks aan stoffen zich op in je bak, waar planten niets mee kunnen. Sommige van die stoffen (afbraakproducten dus van organisch materiaal) vergiftigen je vissen simpelweg. Andere stoffen worden uit het water gevist door rondzwevende bacteriën, die zich dan vermenigvuldigen en in grote aantallen op je vissen kunnen neerstrijken. De gevolgen van zo'n overload aan bacteriën zijn dagelijks te vinden in de ziekte-afdeling van dit forum.

Behalve bacteriën leven er in biofilters ook allerlei andere microscopische beesten. Die verrichten elk zo hun taken. Het één jaagt daarbij op het ander. Het evenwicht dat ontstaat betekent ook dat allerlei ziektekiemen "in check" worden gehouden. Grote ziekte-uitbraken zijn in een goed gerijpte bak met voldoende (= veel!) filteroppervlak om die reden eigenlijk niet aan de orde.

Om je niet teleur te stellen, heb ik er wat uitleg bijgezocht van de verschillende manieren waarop planten en bacteriën werken. Voor de gelegenheid heb ik het e-book Ecology of the planted aquarium voor je afgestoft. Is geschreven door microbioloog/wetenschapper Diana Walstad. Dit boek bulkt van de wetenschappelijke verwijzingen dus er staan op zich wel wat dingen in die we serieus mogen nemen. Bedankt trouwens dat je me hiertoe "dwingt" want er staat een hoop coole info in. Wie dit boek uit zijn hoofd kent, kan zich misschien wel kronen tot plantenkoning van het Aquaforum.

Hier volgen wat citaten en tabellen uit dat boek. (Hoofdstuk: Bacteria) De info overlapt her en der een beetje, maar ik heb even geen zin om deze post tot in de perfectie in te korten. 😛 Kijk maar of je er iets aan hebt.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

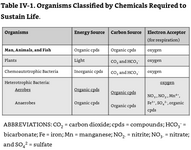

Bacteria that are important in aquariums can be compared with other organisms by the chemicals they use for their metabolic processes (Table IV-1). Animals and heterotrophic bacteria use organic compounds for energy, while chemoautotrophic bacteria use inorganic chemicals. Most organisms use oxygen to accept electrons for respiration.

The metabolic processes of bacteria also result in the conversion of one chemical to another. Some of the chemical conversions important to aquariums are shown in Table IV-2. For example, in the bacterial process of nitrification, ammonium is converted to nitrate.

(...) Decomposition by Heterotrophic Bacteria

The decomposition of organic matter by ordinary (i.e., heterotrophic) bacteria is important to planted aquariums. Organic matter contains all the elements that plants require, but the elements are ‘locked up’ in large organic compounds. Heterotrophic bacteria convert organic matter, whether in the form of fishfood, plant debris, dead bacteria, etc, into the nutrients that plants can use. Some of the conversions that occur are:

Organic Matter ⇒ Inorganic Compounds (Plant Nutrients)

Organic N ⇒ ammonia + CO2

Organic P ⇒ phosphates + CO2

Organic S ⇒ sulfides + CO2

Because organic matter invariably contains carbon, CO2 is always released during decomposition. Moreover, other elements, not just N, P, S, and C, are converted from their organic forms to plant nutrients by heterotrophic bacteria. Organic matter that heterotrophic bacteria feed on comes in two physical forms– particulate organic carbon (POC) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC). POC, which includes fish feces and fibrous plant matter, is harder for bacteria to digest than the much smaller DOC. (Here is where fungi and snails are useful, because they reduce particle size, thereby speeding up the decomposition process.)

Ironically, DOC, which we can’t see, is usually a much larger reservoir of carbon in natural systems, plus it is the form of organic matter from which plant nutrients will be most rapidly released. The average DOC concentration for the world’s rivers is 5.8 mg/l, while the average for 500 Wisconsin lakes is 15.2 mg/l. (For all natural waters the range is 1-30 mg/l.) Almost all DOC and debris in aquariums is in various stages of decay, but the rate of nutrient release may vary considerably. (Heterotrophic bacteria have their own preferences in terms of what constitutes desirable food and a suitable environment.) DOC includes proteins, organic phosphates, and simple sugars, which are metabolized rapidly, probably within hours at the warm temperatures and neutral pH of most aquariums. The less-digestible portion of DOC, such as humic substances, may take months or longer for bacteria to digest. Finally, complete digestion of POC in the anaerobic substrate environment may be impossible, resulting in the gradual accumulation of sediment humus (‘fish mulm’).

Bacteria understandably divert part (20-60%) of the nutrients released by decomposition to synthesize their own cellular material. However, these bacteria also die and decompose themselves. Indeed, in lake water over a 20 day period, four separate and sequential bacteria populations were associated with reed decomposition. There may be several of these recyclings before a nutrient is finally taken up by plants. Aerobic decomposition, which requires oxygen, is much faster than anaerobic decomposition. Thus, air/water mixing and plant photosynthesis stimulate decomposition by adding oxygen to the water. Most bacteria require a neutral pH, such that pH can have a major impact on decomposition. For example, swamps containing Sphagnum (‘peat’) mosses are often very acidic (pH 3 to 4.5), because the plants themselves are acidic.

Bacterial activity and decomposition slow considerably in this acidic environment. Organic matter accumulates, because bacteria are not converting it to gases such as methane, CO2, and hydrogen. The end result is that a Sphagnum swamp gradually fills in with the undigested organic matter. In the final analysis, decomposition in an ecosystem is a summation of many separate, on-going metabolic processes. Thus, in lakes as well as in the established aquarium, decomposition and the release of plant nutrients is typically a steady, stable, and continuous process.

(...) Nitrifying bacteria are chemoautotrophic and differ from heterotrophic bacteria in that they oxidize inorganic chemicals (ammonium and nitrite) to obtain their energy. (Other chemoautotrophic bacteria are H2S-oxidizing bacteria.) Chemoautotrophic bacteria differ from the vast majority of bacteria, which are heterotrophic (heterotrophic bacteria obtain their energy from the decomposition of organic compounds, such as proteins and sugars).

(...) Actually, nitrifying bacteria are similar to plants in that they synthesize the large organic compounds they are made of (proteins, sugars, etc.) from small inorganic compounds like CO2, iron, phosphates, etc. Plants use light energy to fuel the process (photosynthesis); nitrifying bacteria use chemical energy to fuel the process (chemosynthesis).

(...) Nitrifying bacteria are helpful, if not essential, in tanks without plants. However, in planted tanks they compete with plants for ammonia. The energy nitrifying bacteria gain from oxidizing ammonium to nitrates is an equivalent energy loss to plants (see page 111).

(...) Bacteria affect nutrient cycling and the production (and destruction) of inhibitory compounds, such as ammonia, nitrites, acetic acid, and hydrogen sulfide. The fact that we cannot easily see bacteria should not discount their importance in aquariums. Probably the most important bacterial process in the planted aquarium is simply the decomposition of organic matter. The gradual decomposition of organic matter by heterotrophic bacteria into plant nutrients is a natural and continuous process. It seems to work well in my aquariums. While CO2 and other nutrients may be added artificially to obtain good plant growth, controlled decomposition by heterotrophic bacteria converts excess fishfood and debris into nutrients that plants can use. Without recycling by heterotrophic bacteria, organic matter would simply accumulate and be unavailable for plants.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

PS Hier nog een leuk linkje over aquaponics. In de tekst staan berekeningen die de beperkingen aangeven van filteren over planten. (TL;DR: Je moet hele oerwouden creëren wil je enig effect bereiken.) En blijkbaar zijn waterplanten nog een stuk minder efficiënt dan planten die in je bak hangen. Je kunt hieruit denk ik wel opmaken dat een zware bezetting nooit enkel over te laten is aan plantenfiltering. Dat is vragen om problemen. In de praktijk is meestal dan ook sprake van een combinatie met de microbiële/biologische filtering.

https://aquariumscience.org/index.php/6-6-aquaponic-filtration/

Laatst bewerkt:

in de praktijk werkt het gewoon en met led licht kan je tegen woordig tot 10 x meer groei en filter capiciteit realiseren met de zelfde hoeveelheid ruimte

heb ook 10 jaar lang en cement mix bak gehad 100 liter buiten met een gelen lis (groot blok) en goud vissen ook altijd goed gegaan geen water beweging nodig deden de vissen zelf

heb ook 10 jaar lang en cement mix bak gehad 100 liter buiten met een gelen lis (groot blok) en goud vissen ook altijd goed gegaan geen water beweging nodig deden de vissen zelf

Als jij 10x meer groei weet te realiseren met LEDs dan volgens het conventionele denken mogelijk is, kun je heel rijk worden. Dat geheim hebben plantenkwekers nog niet ontdekt namelijk. 😛

En tsja, in de natuur draait ook niet op iedere kuub water een FX6. Daar is de bezetting dan ook naar. Ik betwijfel of er in jouw vijver bovennatuurlijke dingen zijn gebeurd; mooi natuurlijk dat je zo vissen hebt kunnen houden, maar het toont niet aan dat het bacteriënverhaal niet zou kloppen. Ik zeg: geloof de experts maar gewoon. 😉

En tsja, in de natuur draait ook niet op iedere kuub water een FX6. Daar is de bezetting dan ook naar. Ik betwijfel of er in jouw vijver bovennatuurlijke dingen zijn gebeurd; mooi natuurlijk dat je zo vissen hebt kunnen houden, maar het toont niet aan dat het bacteriënverhaal niet zou kloppen. Ik zeg: geloof de experts maar gewoon. 😉

laat het hier bij gino als je denkt het alemaal zo goed te weten de bewijzen van die 10 x zijn bewezen in de zout watr hobby met een refugiumAls jij 10x meer groei weet te realiseren met LEDs dan volgens het conventionele denken mogelijk is, kun je heel rijk worden. Dat geheim hebben plantenkwekers nog niet ontdekt namelijk. 😛

En tsja, in de natuur draait ook niet op iedere kuub water een FX6. Daar is de bezetting dan ook naar. Ik betwijfel of er in jouw vijver bovennatuurlijke dingen zijn gebeurd; mooi natuurlijk dat je zo vissen hebt kunnen houden, maar het toont niet aan dat het bacteriënverhaal niet zou kloppen. Ik zeg: geloof de experts maar gewoon. 😉

Weet je, je moet doen waar je je goed bij voelt. Jij hebt plantjes uit je bak hangen en dat staat nog best leuk. En je hebt er een punt mee dat ze kunnen helpen met de filtering. Doe je ding. 🙃laat het hier bij gino als je denkt het alemaal zo goed te weten de bewijzen van die 10 x zijn bewezen in de zout watr hobby met een refugium

Het gaat me er verder niet om dat ik gelijk zou krijgen. Ik wist 3 jaar geleden nog niks en heb telkens, al lerende, andere standpunten ingenomen. Wil niet per se zeggen dat ik het nu wél bij het goede eind heb. Of dat de bronnen hierboven perfect zijn. Maar als e.e.a. in twijfel getrokken wordt (wat dus prima is) is het wel zo handig als er een aannemelijk verhaal tegenover wordt gesteld. In het rijk der feiten betekenen persoonlijke overtuigingen niets.

led geeft niet veel warmte af daar door kan je per vierkante meter veel meer wattage geruiken een kessil lamp van 300 watt of een tl buisje van 30 watt is gewoon de fotosynthese 10 x verdubbelen dat is het idee..Weet je, je moet doen waar je je goed bij voelt. Jij hebt plantjes uit je bak hangen en dat staat nog best leuk. En je hebt er een punt mee dat ze kunnen helpen met de filtering. Doe je ding. 🙃

Het gaat me er verder niet om dat ik gelijk zou krijgen. Ik wist 3 jaar geleden nog niks en heb telkens, al lerende, andere standpunten ingenomen. Wil niet per se zeggen dat ik het nu wél bij het goede eind heb. Of dat de bronnen die ik hierboven perfect zijn. Maar als e.e.a. in twijfel getrokken wordt (wat dus prima is) is het wel zo handig als er een aannemelijk verhaal tegenover wordt gesteld. In het rijk der feiten betekenen persoonlijke overtuigingen niets.

Ik snap je verhaal, maar je krijgt niet zomaar eventjes een 10x hogere opbrengst door aan de lichtknop te draaien. Er zit een plafond aan de maximale hoeveelheid straling die planten kunnen verwerken en daarmee aan de maximale dagelijkse toename van plantenmassa. In de link die ik gaf heeft iemand uitgerekend hoeveel dat ongeveer is. Je mag en kan dergelijke info negeren, maar mag ik je dan wijzen op het bestaan van paralleluniversa waarin de natuurwetten flexibeler zijn dan hier? ;-p Daar is filtratie veel makkelijker, zijn dit soort discussies korter, etc. Ehehe...led geeft niet veel warmte af daar door kan je per vierkante meter veel meer wattage geruiken een kessil lamp van 300 watt of een tl buisje van 30 watt is gewoon de fotosynthese 10 x verdubbelen dat is het idee..

tuinkabouter

Well-known member

Niet geheel…led geeft niet veel warmte af daar door kan je per vierkante meter veel meer wattage geruiken een kessil lamp van 300 watt of een tl buisje van 30 watt is gewoon de fotosynthese 10 x verdubbelen dat is het idee..

Maar dat verhaal is hier niet van toepassing en gaan we meteen vrij diep in op iets wat vrij ver afwijkt van dit topic

You haven't joined any rooms.

Installeer de app

Hoe de app op iOS te installeren

Bekijk de onderstaande video om te zien hoe je onze site als een web app op je startscherm installeert.

Opmerking: Deze functie is mogelijk niet beschikbaar in sommige browsers.